If you’ve been following the Devops Weekly newsletter, DevOps-like conferences or if you’re just really interested in technology, you’ve probably heard of unikernels being mentioned a few times. In the last few months, its popularity has greatly increased.

But, what are these ‘unikernels’ really? And, is it something for me?

I struggled with that question. Both defining a unikernel and answering the question ‘who are they for’?

What are unikernels#

The single source of truth is Wikipedia with a cryptic explanation, but let’s start there.

Unikernels are specialised, single address space machine images constructed by using library operating systems. A developer selects, from a modular stack, the minimal set of libraries which correspond to the OS constructs required for their application to run.

These libraries are then compiled with the application and configuration code to build sealed, fixed-purpose images (unikernels) which run directly on a hypervisor or hardware without an intervening OS such as Linux or Windows.

All clear, right?

Well, if you’re like me, that may not tell you much. So here’s my explanation of unikernels.

Let’s step back a little first and follow this example. Let’s say you’re a developer writing a PHP application. When you run your PHP (or Ruby, or Node, or Perl, or …) application, you’re essentially running:

- Your language interpreter: PHP, Perl, Ruby, …

- Which calls system level APIs of your operating system

- Some of these API calls require other level privileges, forcing context switches for your application … (user space vs. kernel space)

- Which is all running on an operating system like CentOS, Debian, Ubuntu, …

- Which is probably a Virtual Machine on VMware, Xen, KVM, …

- Which is run by its own virtualisation operating system (ESXi, Xen Hypervisor) …

- Which in turn is running on hardware

- Which is bootstrapped by a BIOS or UEFI

Honestly, if you’re thinking about all the levels an application is built upon, it’s a miracle things even work.

But they do. And they work pretty well and with reasonable performance. But you have to admit, there are a lot of layers between the hardware that’s supposed to be powering your application and the application itself.

That’s what unikernels as a concept try to solve: remove the bloat that separates hardware from application. Have “just enough” of the Operating System to run your code, nothing more.

There’s a great paper that sums it up nicely:

The idea [of a unikernel] is that you look at cloud guests just like you would look at single-application hardware.

A unikernel tries to remove some of complexities that modern operating systems bring. Because they are “general purpose” operating systems (like just about any Linux or Windows distribution), they also come with drivers, packages, services, … that may not apply to your application, but are generally considered OK to have on every OS install.

Even core modules in the Linux kernel don’t apply to every installation. Things like USB drivers are useless in a virtualised “cloud” environment, but are still included in the kernel.

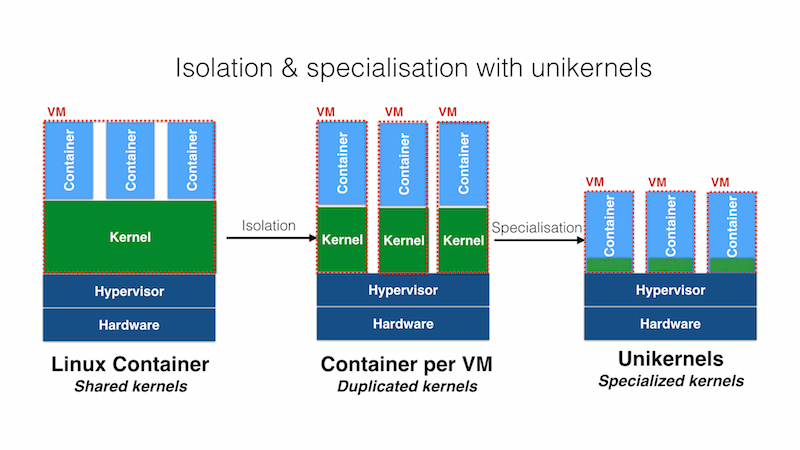

Compared to containers and virtualisation, the excellent road to unikernels presentation pictures it like this:

(Source: road to unikernels )

Unikernels have a couple of advantages over general purpose operating systems like Linux;

- Improved security: only the core of the OS is implemented, no video or USB drivers that aren’t needed and could be a source of intrusion.

- Very small footprint: imagine being able to remove 95% of the kernel size, simply because your application doesn’t need it.

- Specialised implementations: you know your application and you can tweak and run your kernel exactly the way you want it.

- Quick enough to be “Just in time ” to summon a unikernel live (similar to live spawning Docker instances), with boot times less than 1 second.

This very nature makes unikernels an excellent candidate for microservices.

Removing layers of complexity with unikernels#

If what you’re after is an application that runs with as little overhead as possible, you may want to consider writing it as a unikernel.

To do so, you use a library operating system. A library OS gives you the tools to create your own unikernel. The most noticeable ones are MirageOS (which actually coined the term “unikernel”) and Rump Kernels . They are both essentially a set of standardised drivers and libraries so you don’t have to reinvent things like a TCP stack, a persistent storage layer, …

Unikernels are specialized OS kernels that are written in a high-level language and act as individual software components. A full application (or appliance) consists of a set of running unikernels working together as a distributed system.

MirageOS is based on the OCaml language and emits unikernels that run on the Xen hypervisor.

queue.acm.org: Unikernels: Rise of the Virtual Library Operating System

The most popular languages nowadays to write a unikernel seem to be:

These aren’t new programming languages. With the exception of Go and Rust, they’ve been around for more than 15 years.

In order to make the OS and the application run as smoothly as possible, these unikernel libraries need a kernel footprint that is as small as possible.

Today, that’s possible because of virtualisation. Because an Operating System like Xen or VMware can do the work of translating the different hardware models into a defined set of virtualised hardware, a unikernel can be optimised for just that specific set of virtual hardware.

Unikernels leverage the advantages of virtualisation to create an operating system that’s as specialised and optimised as possible.

The result of an application written in OCaml with the MirageOS set of libraries to form a “unikernel” can be summarised like this:

The compiler can then output a full stand-alone kernel instead of just a Unix executable. These unikernels are single-purpose libOS VMs that perform only the task defined in their application source and configuration files, and they depend on the hypervisor to provide resource multiplexing and isolation.

queue.acm.org: Unikernels: Rise of the Virtual Library Operating System

The result is that you run a unikernel, a small but dedicated operating system, to run (parts of) your application. If an update to your application or configuration is needed, you compile a new version of your source code to a new unikernel and you deploy that new version. A new security release? Re-compile and deploy.

This makes coordination and orchestration of deploys harder at the benefit of running a more efficient application.

This essential creates the concept of immutable servers: an application server no longer stores state and can be thrown away and rebuilt at your convenience.

One approach may be to start running unikernels in docker containers , but aren’t we adding another layer of complexity that we should try to avoid? On the other hand, Docker adds ease of use and deployments to the mix that may make the trade-off worthwhile.

Who should run unikernels?#

To be perfectly honest, the answer to me isn’t exactly clear yet. I think it’s fair to say that if you’re currently deploying web applications built on WordPress, unikernels may be a bridge too far.

On the other hand, the benefits of unikernels are evident but require a completely different mindset to managing your infrastructure, a different skillset in creating these kind of applications and kernels and require a very deep understanding of concepts that are mostly foreign to us now: immutable infrastructure.

Maybe in 2, 5 or 10 years we’ll deploy unikernels like they’re the new normal. Right now, I think it’s for a very select niche set of users that are looking for highly specialised and secure applications. For the most common use cases, either a Virtual Machine (or, if you’re already on the bandwagon: docker containers) are probably what you’ll be focussing on.

More reading material on Unikernels#

If you’re interested in the subject, here are some other links I can recommend you spend your time on: